Featured Stories

11 Best Free AI Sexting Apps in 2024– Experience Spicy Sex Chat (For Android & iOS)

Looking for the Best safe and secure Free AI Sexting Apps? Bored watching Porn & Upto something new? Then Try Best…

Popular SEO Guides

11 Best Free AI Sexting Apps in 2024– Experience Spicy Sex Chat (For Android & iOS)

Looking for the Best safe and secure Free…

5 Best Cheapest VPS Hosting India in 2024

Do You Want to Buy the Best and Cheapest…

9 Best Cheap Offshore VPS Hosting Servers in 2024

A reliable and affordable Virtual Private…

How To Find Out Who An Unknown Caller?

Are you frustrated with spam calls or…

Editor’s Picks

Featured Videos

11 Best Free AI Sexting Apps in 2024– Experience Spicy Sex Chat (For Android & iOS)

Looking for the Best safe and secure Free AI Sexting Apps? Bored watching Porn & Upto something new? Then Try Best Free Ai…

Tranding posts

11 Best Free AI Sexting Apps in 2024– Experience Spicy Sex Chat (For Android & iOS)

Looking for the Best safe and secure Free AI Sexting Apps? Bored…

5 Best Cheapest VPS Hosting India in 2024

Do You Want to Buy the Best and Cheapest VPS Hosting India? Are you…

9 Best Cheap Offshore VPS Hosting Servers in 2024

A reliable and affordable Virtual Private Server (VPS) hosting service…

How To Find Out Who An Unknown Caller?

Are you frustrated with spam calls or telemarketers calling you so…

16 proven digital marketing strategies to boost your silver jewellery business

Silver jewellery has always been a popular choice among consumers.…

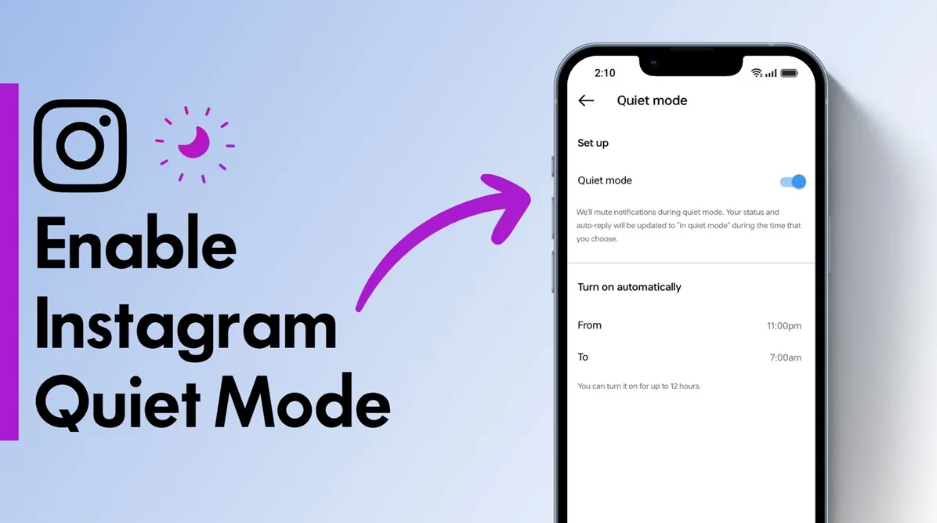

How to Enable Quiet Mode on Instagram

In today’s fast-paced digital world, social media can sometimes…

Best VPNs for YoMovies

Are you a movie enthusiast who loves streaming the latest films and TV…

How to Fix a USB Wi-Fi Adapter That Keeps Disconnecting

In an increasingly connected world, a reliable Wi-Fi connection is…

About Us

Onlyloudest is a Web Portal to provide you with some deep and excoriating knowledge about various facets of life. Information is an important and integral part of our life, and we work hard to give you exotic insights about everything. The only thing we want to change is how we circulate and consume information.

- Redefining Knowledge Sharing

- Striving for Excellence

- Global Impact